Protoplasm as the Living Stuff

Biologists today focus on DNA and ways that genes influence life. In the 19th century, the nucleus looked relatively stable and separated from the rest of the cell, while the protoplasm seemed to be dynamic. Protoplasm, some leading biologists suggested, must be the stuff of life.

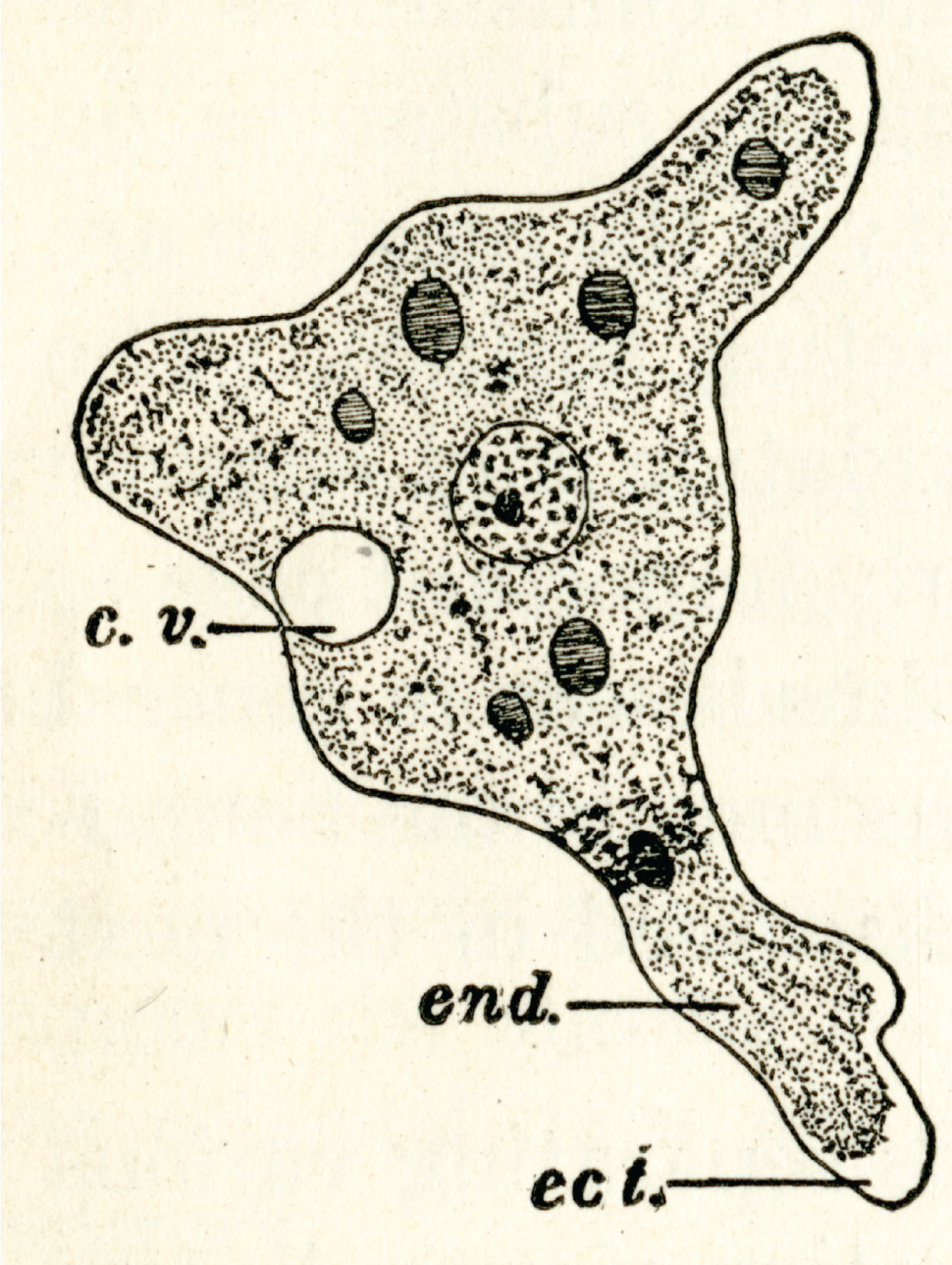

Protoplasm flows and moves, a viscous substance inside cell walls. Apparently constant motion suggested that protoplasm causes cells to move, grow, divide (with help from the nucleus), and interact with each other. Attention shifted to the insides of individual cells, such as white blood cells or amoebae, instead of cell walls or membranes.

HoverTouch to magnify

HoverTouch to magnify

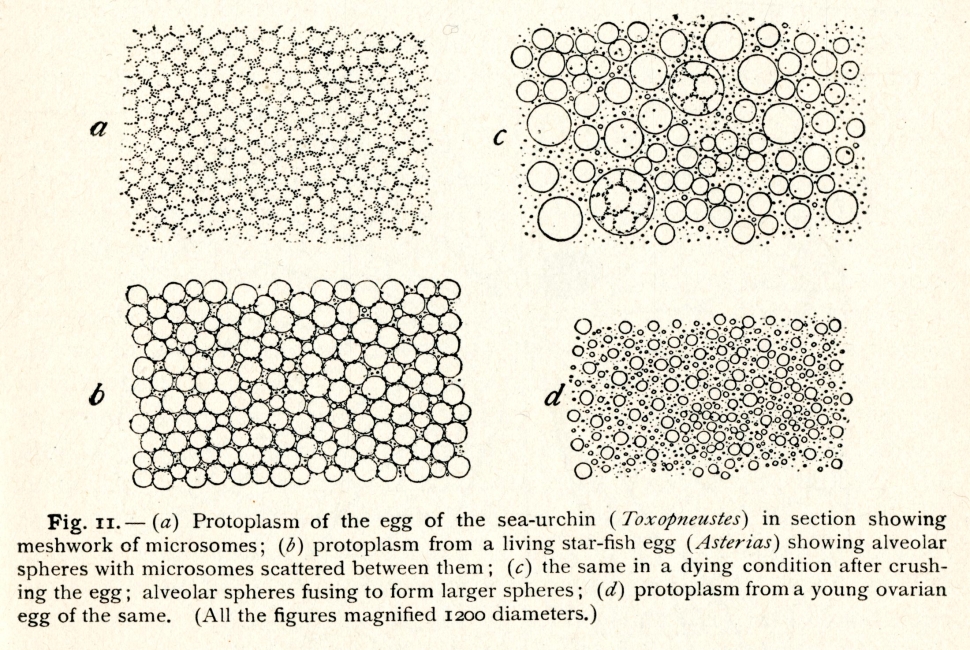

Fig. II. - (a) Protoplasm of the egg of the sea-urchin (Toxopneustes) in section showing meshwork of microsomes; (b) protoplasm from a living star-fish egg (Asterias) showing alveolar spheres with microsomes scattered between them; (c) the same in a dying condition after crushing the egg; alveolar spheres fusing to form larger spheres; (d) protoplasm from a young ovarian egg of the same. (All the figures magnified 1200 diameters.)

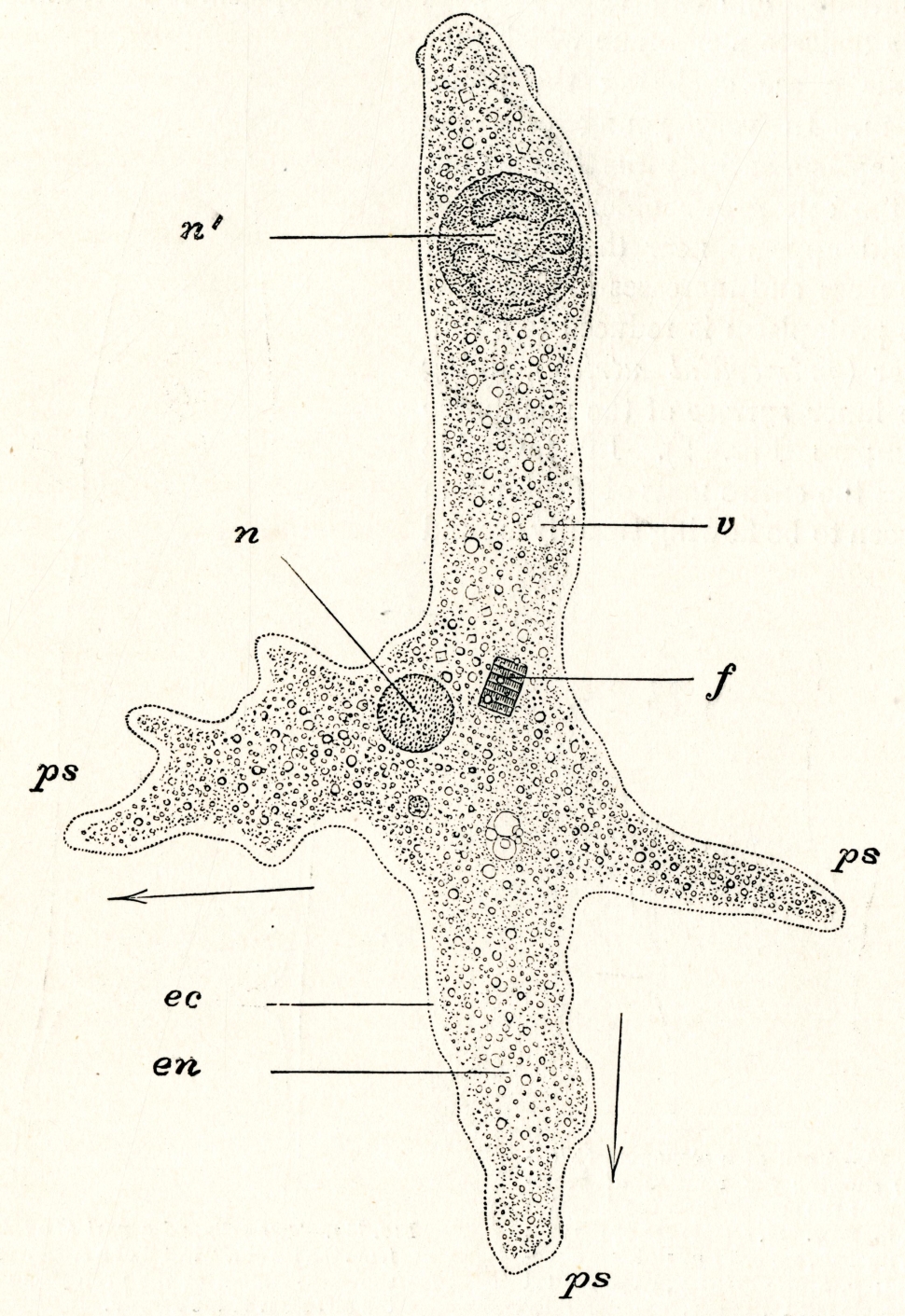

An amoeba consists of a single cell and offers an ideal way to study the roles different cell parts play. An amoeba seen through the 19th century microscope looked like a migrating blob of protoplasm with a nucleus, lacking a rigid cell wall.

HoverTouch to magnify

HoverTouch to magnify

Ideas about what made up a “cell” changed from focusing on the wall that Hooke had emphasized to the moving substance inside the cell. An amoeba, with protoplasm as its dominant feature, could be seen as an ideal “minimal cell.”

HoverTouch to magnify

HoverTouch to magnify

- Wilson, Edmund Beecher. 1899. “The Structure of Protoplasm.” Science 10 (237): 33-45. Page 36, Figure 1, a and b.

- Sedgwick, William Thompson, and Edmund Beecher Wilson. An Introduction to General Biology. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1886. Page 27, Figure 15.

- Sharp, Lester W. An Introduction to Cytology. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1926. Figure 9, Page 44.